Saints Paul and Augustine

Part Three (i):

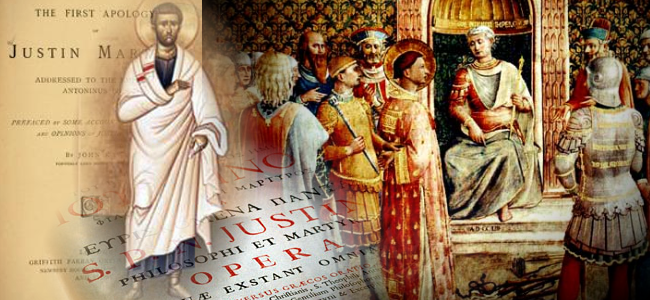

Paul and Justin Martyr

“When [Justin] contrasts the life that they led in paganism with their Christian life (I Apol., xiv), he expresses the same feeling of deliverance and exaltation as did

newadvent.org

James A. Kelhoffer has recognised certain similarities between the thinking of Sts. Paul and Justin, in “The Apostle Paul and Justin Martyr on the Miraculous: A Comparison of Appeals to Authority”: http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:385562/FULLTEXT01.pdf

At the very beginning of this article, he writes:

THE SUBJECT OF MIRACLES has too often been ignored or overlooked in scholarly discussions of early Christian ity.1 This article focuses on the writings of Paul and Justin Martyr, in part because these authors exemplify points of both continuity and development from the writings of the NT to the early patristic literature.2 Although these authors employ different genres,3 there is no reason to suspect that either author’s choice(s) of genre has necessarily limited what he wished to write concerning the miraculous. Part of what is to be offered here is a subtle argument that Paul and Justin did, in fact, have true, then, whether explicitly or implicitly, it is an oversimplification to interpret Paul solely as a herald of the word of the gospel, or Justin only as a rationally-minded apologist.

The analysis to follow builds upon a seminal essay by Paul Achtemeier,5 as well as more recent analyses by Ramsay MacMullen,6 Bernd Kollmann,7 Stefan Schreiber,8 and others,9

and focuses on three questions: In what ways do Paul and Justin Martyr refer to miraculous phenomena? What common assumptions do these authors hold about the performing of miracles, especially with regard to appeals to authority? To what ends, or with what goals, do Paul and Justin refer, usually in passing, to the miraculous? ....

[End of quote]

Some further comparisons can be found in Thomas V. Mirus’ article, “Church Fathers: St. Justin Martyr”: https://www.catholicculture.org/commentary/articles.cfm?id=645

The Dialogue, by far Justin’s longest work, can be divided roughly into three parts. In the first, Justin shows the temporary and symbolic nature of the old Law. In the second, he shows how adoration of Christ as God is consistent with monotheism. In the third, he proves that Christians, not Jews, are the new Israel and the recipients of the promises of God’s covenant.

Some of the points touched on again and again throughout the Dialogue are as follows: Justin contrasts physical circumcision (which he says was to set the Jews apart for suffering!) with circumcision of the heart, which is an attribute of Christians. He finds in the Jewish prophecies two advents of Christ, the first dishonorable and the second glorious, and points out symbolism of the Cross in the Old Testament. He echoes the teaching of St. Paul that the Jewish Law was given as a burden because of the hardness of hearts. He finds many names given to the Son of God in the Old Testament: Angel, Wisdom, Day, East, Sword, Stone, Rod, Jacob, Israel.

Justin gives a detailed exegesis of Psalm 22 (“My God, my God, why have You forsaken me?”), showing how it applies to Christ and why Christ quoted it on the Cross.

As St. Paul parallels Christ with Adam, St. Justin parallels Mary with Eve (according to Quasten he is the first Christian writer to do so):

[Christ] became man by the Virgin, in order that the disobedience which proceeded from the serpent might receive its destruction in the same manner in which it derived its origin. For Eve, who was a virgin and undefiled, having conceived the word of the serpent, brought forth disobedience and death. But the Virgin Mary received faith and joy, when the angel Gabriel announced the good tidings to her that the Spirit of the Lord would come upon her, and the power of the Highest would overshadow her: wherefore also the Holy Thing begotten of her is the Son of God; and she replied, ‘Be it unto me according to thy word.’

[End of quotes]

And Robert M. Haddad tells of this, in “The Appropriateness of the Apologetical Arguments of Justin Martyr”:

Ever since Apostolic times, Apologetics has been a part of the life and mission of the Church. Luke-Acts was an attempt to provide an apologia to whoever Theophilus might have been. .... We read in Acts 28:23 how St. Paul, while in Rome, received people “... at his lodgings in great numbers. From morning until evening he explained the matter to them, testifying to the kingdom of God and trying to convince them about Jesus both from the Law of Moses and from thee prophets”. Justin inherited this spirit, at a time when those who knew the apostles were now advanced in years and new men with new thoughts needed to rise to engage with a Graeco-Roman world both more aware of and hostile towards Christianity. ....

Finally, Cullen I. K. Story, writing of “The Cross as Ultimate in the Writings of Justin Martyr, has this to say (Introduction, p. 18):

While it is true that his seaside friend had led Justin to know God, the Ultimate Reality, still that merely marked the beginning of Justin's Christian experience. From his extensive works it is clear that in a way similar to the apostle Paul (Gal. 2:19-20; 6:14; I Cor. I :23-24; 2:2) Justin found life and its meaning to be centered in the crucifixion of Jesus. Biblical tradition, he affirmed, not only points to the ultimate truth that Gad is, but to the Cross as the ultimate truth that Gad becomes, i.e., the tradition points to a crucified Christ. ....

Part Three (ii):

Justin Martyr and Saint Augustine

“As St. Justin Martyr notes, free will has to exist for God’s rewards and punishments

to be Just. St. Augustine reaffirms this, and applies this principle, explaining that

those actions done to us that we do not will, cannot be imputed to us as sins”.

Sts. Justin and Augustine are commonly compared and contrasted.

For example, there is John Mark Reynolds’ “Justin Martyr: Not Just Dead, Just Not Augustine”:

... Justin lacks Augustine’s rhetorical skill, but this can be a benefit. Augustine has left us countless memorable passages, but Justin provided the framework for arguments that Augustine will flesh out. Augustine’s rhetoric is from a very particular period of time, while Justin writes with a spare style that is never beautiful, but is always clear. Oddly, he is sometimes less dated than Augustine. ....

[End of quote]

Michael M. Christensen will trace the doctrine of “Original Sin from Justin Martyr to Augustine”:

In an article, “Justin Martyr: Convert from Heathendom”, at:

Justin understood, after his conversion, that these questions and this deep unsatisfied longing for something he knew not what, was the work of Christ in his soul. It is doubtful that God ever brings anyone to salvation and the knowledge of Christ without creating in him a deep longing, an unsatisfied thirst, a hunger for something which one does not have. Augustine, three centuries later, put it this way in his Confessions: "My soul can find no rest until it rest in Thee." This longing, finally, is born out of the knowledge of sin and the hopelessness and emptiness of one's life brought about by the hopelessness of sin. Salvation is by faith in Christ; but only the empty sinner needs Christ; only the thirsty sinner drinks at The Fountain of Living Waters; only the hungry sinner eats The Bread of Life; only the laboring and heavy laden come to Christ to find rest for their souls. It is the general rule of the Holy Spirit to bring to faith in Christ by sovereignly showing the sinner the need for Christ.

That Justin had this deep longing is not strange. That it was a part of his life for ever so many years before peace came is a remarkable providence of God.

[End of quote]

the following “Conclusion” is reached:

Conclusion

Admittedly, free will is a bit of a mystery. We don’t fully grasp what it is, or how it works. It puzzles theists and atheists alike. But we can be sure that it exists, in part because it is necessary for God’s Justice, and in part because we cannot coherently speak of it not existing (any more than we can coherently speak of a self-caused universe arising without God).

As St. Justin Martyr notes, free will has to exist for God’s rewards and punishments to be Just. St. Augustine reaffirms this, and applies this principle, explaining that those actions done to us that we do not will, cannot be imputed to us as sins. What matters is not what happens to us, but what we will. Thus, it is wrong to condemn the virgins of Rome as fornicators when they were raped. It would be infinitely more wrong to send them to Hell for being raped.

All of this, in addition to being logically necessary, is self-evident. That is, each of us experiences free will, even if we choose to deny it. It’s for this reason that even those, like Luther or Calvin, who set out to deny free will (at least as pertains to issues tied to salvation) cannot help but speak as if it exists. Because it does. And we can observe it does.

No comments:

Post a Comment